- Home

- Kirker Butler

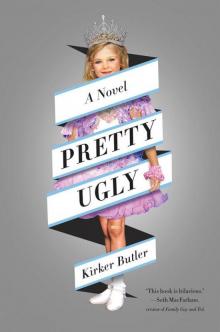

Pretty Ugly: A Novel Page 2

Pretty Ugly: A Novel Read online

Page 2

Three months later, the winner of the pageant, Missy Hale, was forced to relinquish her crown after informing the pageant committee she had married her boyfriend, who she was “pretty sure” was the same guy who got her pregnant. Promoted to First Runner-up, Miranda was told she should be ready to take the crown in the unlikely event that the new queen, former First Runner-up Alexandra Black, was not able to fulfill her duties. And then, just as if God Himself had ordained it, six days before Christmas, Alexandra—along with her uncle, sister, mother, and mother’s boyfriend—were arrested for felony production of crystal meth with intent to distribute.

Miranda’s reign lasted only seven months, but it was one of the most exciting periods of her life. Her picture was in the paper almost every other week, and everywhere she went little kids asked for her autograph. At school, she immediately skipped several rungs of the social ladder and soon went from being a dedicated yet anonymous 4-H member to being recruited for Drama Club vice president. Her prefame friends accused her of becoming “two-faced” and “conceited.” Miranda just shrugged it off as jealousy, but they weren’t wrong. She was acting different, because she was different. Miranda was a local celebrity now—and she liked it. A lot.

“Look,” she told Lori Caldwell, a close friend since kindergarten, “I have responsibilities now. People count on me. And that means I’m going to have less time for my friends. And if you can’t accept that, then maybe it’s not me who’s being conceited. Maybe it’s you for not understanding what I’m going through.”

It’s like she said in that interview with the school paper, “Being me can be overwhelming sometimes. I mean, I can totally relate to the pressures of someone like Princess Diana.” She paused to let the scrawny sophomore reporter, who had once tried to kiss her on a church hayride, really hear her. “It just never ends, you know? Someone’s always wanting a picture or a hug or just a kind word. But that’s my job now, I guess, touching people’s lives and stuff. And I’m just grateful to have it.”

For seven glorious months, Miranda got to breathe the rarified air of royalty. It’s like she said in her memoir: “I was famous, which meant I was special. And in a world that reveres such things, why wouldn’t I want the same for my daughter?”

chapter two

“Of course your children are beautiful. But are they sexy enough?” Miranda Ford Miller repeated the words out loud to make sure she’d read the ad correctly. What an appalling question, she thought. “As if I don’t already have enough to think about.”

After eight and a half years and three hundred sixty-three pageants, Miranda was pretty sure she’d thought of everything, but this had never even occurred to her. What kind of pageant mother was she, anyway?

“Dammit,” she whispered, drumming her fingers on the faded yellow Formica of her kitchen table. If she’d overlooked something as fundamental as her nine-year-old daughter’s sex appeal, what else had she missed?

To be sure, Miranda had done a lot right. Her daughter, Bailey, was a legend on the Southern United States pageant circuit, having racked up one hundred twenty-eight wins and ninety-six runner-up titles in her career, placing her fifth on the all-time winners’ list according to the Southern Pageant Association’s Web site. A born competitor and naturally (for the most part) beautiful, Bailey had a commanding stage presence and carried herself with the grace and elegance of a high-heeled gazelle. Her talent, a grueling tribute to Cirque du Soleil’s KÀ

set to Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain,” was provocative and perfectly executed, and no child flirted with the judges as intuitively as Bailey Miranda Miller. She was the total package. But according to Glamour Time Photography Studio, that wasn’t enough. Apparently, she also had to be sexy.

Are your children sexy enough?

The words stuck in her head like a bad song.

“I can’t deal with this right now,” she said, and tossed the ad aside like everything else that bothered her. Adjusting the pumpkin and turkey table runner, which was only a few months from turning a corner and being appropriately seasonal again, Miranda pretended to ignore the three days’ worth of dirty dishes snaking out of the sink and across the cracked tile of the counter to focus on what was important: the weekend and the 29th Annual Little Most Beautiful Princess Pageant. Bailey would be relinquishing her crown as Junior Miss Beautiful, and not a moment too soon. What with her pushing seventy-five pounds and all.

Miranda was not proud of how she judged her daughter’s appearance, but the harsh reality was that the average nine-year-old girl weighed sixty-three point eight pounds. Bailey was in the eighty-fourth percentile for weight, and that made her vulnerable. No doubt the other mothers had noticed Bailey’s extra bulk just like Miranda noticed the numerous flaws in their girls. Melody Norton’s hair extensions looked (and smelled) like the horsehair they were; Karliegh Sandefur’s flipper (the dental prosthetic that filled in the gaps of her missing baby teeth) only highlighted the fact that her new adult teeth were stained and crooked; and all the makeup in the world couldn’t hide the fact that JoBeth Kanton was just plain ugly. But all of that was better than fat. Fat was unforgivable. Fat was fatal.

Parents who entered their overweight children in beauty pageants were worse than parents who encouraged their handicapped children to play sports. They think they’re doing the right thing, showing the kids that they’re “just like everyone else,” but everyone else, including the handicapped kids, knows they’re not. It just slows everything down and makes people uncomfortable. “Some parents,” Miranda liked to say, “shouldn’t be.”

Most overweight girls who participated in pageants did so because their parents thought it would be good for them, which was akin to saying, “Hey, honey, you know how everyone at school makes fun of your weight? Well, I think you’d feel much better about yourself if you put on a bathing suit and stood next to a cheerleader on a stage under a spotlight in a room full of strangers.” Miranda called them charity girls. Parents of the serious competitors were usually pretty tolerant of charity girls because they never won anything except maybe Congeniality, and there wasn’t a cash prize for that. And that was the problem. Pageants were expensive, and if Bailey didn’t remain diligent, and count every calorie, she would balloon right out of a career.

Miranda had started to suspect Bailey was eating an extra lunch at school. At the very least she was consuming more than the four-hundred-calorie meals Miranda had paid a nutritionist to prepare and deliver every morning. And she was very close to proving it before being asked to leave the school grounds for loitering. Miranda had tried everything to help her daughter lose weight: a gym membership that came with ten private pole-dancing lessons; a consultation with an overly puritanical plastic surgeon who refused to even discuss performing liposuction on a child, even when Miranda offered to pay double; and the “health clinic” in Puerto Rico where Tina Murray had taken her seven-year-old daughter Sephora to get excess fat removed from her love handles and injected into her lips. Miranda decided to put a pin in Puerto Rico when Sephora contracted a still unidentified infection that left her seventy percent deaf in one ear and half of her bottom lip permanently blue.

She then tried a fourteen-hundred-dollar custom-made neoprene sleep suit that was promised to sweat out excess water weight. But after a series of night terrors where Bailey dreamed she’d been thrown in the trash, followed by a two A.M. trip to the emergency room for dehydration, the suit was put on eBay. Despite her best efforts, the sad fact remained that Bailey was getting fat, and Miranda would just have to add that to the growing list of disappointments in her life.

She glanced again at the Glamour Time Photography ad sitting like a cherry atop a shit sundae of past-due bills. Again, Miranda tried to ignore it and looked around her kitchen wishing it were bigger. And newer. And part of a larger house. In Thoroughbred Acres. If Bailey hadn’t won that new dishwasher at the Gorgeous Belles and Beaus Pageant (Augusta, Georgia), the room would be downright shameful. Miranda briefly co

nsidered washing a few dishes, just to take her mind off her failure as a mother, but the ad wouldn’t leave her alone. Needing a distraction, Miranda decided she should start packing for the weekend, but a sharp kick in her stomach nearly took her breath away. Rubbing her belly, she realized she hadn’t eaten in nearly four hours.

“Brixton,” she said quietly, feeling her baby move inside her, “you’ve got to calm down, sweetheart. Lunch isn’t for another”—she looked at the clock—“half hour.”

Aggressively nontraditional baby names had become a trend at pageants all across the South, each one desperately transparent in an attempt to be quirky and memorable: Maelynn, Shelsea, Brinquley, LaDoris, Braethern, Gradaphene, Hendrix, Stylus, Dorsalynn, Orabelle, Gunilla, Kindle, Haylorn, JubiLeigh, Harlee, Davidson … Ridiculous all, but Brixton was different. Brixton was divinely inspired on a road trip to the Prettiest Girl in the World Pageant (Valdosta, Georgia).

Trailing a battered yellow dump truck filled with charred bricks from a razed crematorium, Miranda thought, There must be a ton of bricks in that truck. The words “bricks” and “ton” tumbled around in her head, and when she put them together it sounded a lot like poetry. A bumper sticker on the back of the truck asked WHERE IS YOUR DESTINY? and listed the Web site for one of those Six Flags Over Jesus megachurches Miranda disliked so much. Seeing the word “destiny” as the name “Brixton” formed itself in her brain was such an obvious and powerful sign from God that even an atheist would be compelled to rethink some things. Miranda decided right then and there that if she ever had another girl, she would name her Brixton Destiny Miller.

Her husband, Ray, wasn’t so sure. “Don’t you think it sounds a little … porny?”

Miranda did not.

When Bailey won her first pageant, Baby Princess Bar-B-Q Fest (Owensboro, Kentucky), at the age of seven months, Miranda told Ray she was ready to have another girl.

“All I want to do is make princesses, Ray! I want a houseful of princesses!”

Within two months she was pregnant, but when the child was born, a healthy and happy little boy they eventually named J.J. (which didn’t stand for anything), Miranda fell into a bout of postpartum depression so deep she could barely see the sun. For the first four weeks, Miranda could not bring herself to hold her baby boy for longer than a few minutes at a time. Six years later she still found it difficult to speak to him in anything longer than curt, declarative sentences. When their second son, Junior Miller, was born fourteen months later, her despair multiplied exponentially.

Spending quality time with her sons became a never-ending struggle. Little girls liked shoes, playing dress-up, having their hair and makeup done, things Miranda understood and was good at. Little boys liked frogs and dirt and farting. How could she possibly be expected to relate to that?

Every now and then, Miranda’s pastor would drop by to check in on her. They’d sit on the screened-in back porch and chat. She’d offer him a piece of pie and a glass of sweet tea, and he’d attempt to explain how the mother/son relationship is one of the most sacred in all humankind, using Jesus and Mary as his primary example.

“First of all,” she said, laughing good-naturedly, “I dare you to spend ten minutes with these boys and then compare them to Jesus. I’m kidding, of course. They’re good boys, and their father looks out for them. Not unlike Jesus. And my mother watches them a lot, too. So they’re fine. I’m not worried.”

The young pastor smiled and sipped his tea, and tried to explain that Miranda was neglecting sixty-six percent of her children.

“Well, first of all, I wouldn’t say I’m neglecting them,” she said. “I love them. I love them more than anything. They’re my children, for heaven’s sake. I just don’t have anything in common with them.” And besides, she thought, when Brixton is born, that number will drop to fifty percent, which is probably pretty close to the national average.

When the ultrasound technician pointed out Brixton’s blurry gray fetal vagina, Miranda practically leapt from the table. She rushed home, dragged Bailey’s old baby pageant outfits from the attic, and meticulously laid them out on every available surface of the living room. Most of the outfits, like the furniture they lay on, were shamefully outdated and needed to be replaced, but just seeing the tiny dresses with their starched crinolines and ruffled bloomers, or the hand-stitched beadwork on the Indian headpiece and matching sequined leggings, made Miranda giddy for the first time in years.

Mistakes had been made with Bailey, obviously, but Miranda was determined not to repeat them with Brixton. And if that meant starting in utero with a strict meal schedule, then so be it.

“If Brixton learns in the womb that meals are to be eaten at specific times,” she explained to Ray, “then maybe she’ll be born with the nutritional discipline that Bailey obviously lacks.”

Ray just nodded. He’d learned to not question Miranda’s plans for the girls.

“Mom, what are you doing?”

Miranda jumped and grabbed her tummy.

“Oh, my God, Bailey!” Miranda said, catching her breath. “Don’t sneak up like that, sweetheart. You’re going to give Mommy a miscarriage.”

The nine-year-old stood in the doorway and shrugged. “Sorry.”

Her honey blond hair hung in front of her face like a veil, and she made no effort to move it. The pink Juicy sweat suit she’d won at last year’s Pride of Paducah Pageant (Paducah, Kentucky) had become a bit snug, but it perfectly matched the running shoes Miranda got free with Bailey’s gym membership. “I’m hungry.”

Miranda took a deep breath and tried to be encouraging. “I’m sure you are, sweetie, but you’re competing this weekend, and we talked about this. You’re up to seventy-five pounds. Which is a lot more than those other girls.”

“Yeah, but most of those girls have been bulimic since birth. They’ll probably never be seventy-five pounds.”

“Well, honey, not everyone can be blessed with an eating disorder,” Miranda said. “Some of us have to work to stay thin.”

Bailey pushed the hair from her face so her mother could see how genuinely appalled she was. “Mom, that’s not funny.”

“You’re right. I’m sorry. I’m just a little hormonal.” Miranda sighed. “Okay. Go do your workout, twenty minutes on the elliptical, and I’ll steam you some carrots.”

The girl stared at her mother before letting her hair fall back into her face and trudged across the kitchen to a door on the far end of the utility room.

“I love you, sweetie!” Miranda called after her. “You’re a beautiful champion!”

“Yep!” Bailey called back, her fist raised in mock triumph. “I’m a winner!”

“See if you can push yourself and do twenty-five minutes,” Miranda yelled, but her daughter slammed the door, cutting her off.

Bailey took a deep breath and locked the door behind her. Kicking off her shoes, she dug her toes deep into the thick white shag carpeting and looked out into a sea of rhinestones. Every surface was covered with trophies, sashes, plaques, and crowns. In one corner, an old toy chest was filled with smaller, lesser trophies that didn’t warrant prime visibility: Best Hair (First Runner-up), Best Smile, Daviess County Second-Grade Spelling Bee Champion. Framed photographs of Bailey being crowned, holding fans of cash, and posing with “celebrity” judges (regional TV news anchors) covered the walls. The ceiling was a rainbow of contestant ribbons. It looked like the rec room of an elegant hoarder. The only nonpageant items were an old futon and a SOLE E35 elliptical trainer Miranda got from a neighbor who’d caught her husband cheating and was giving all his stuff away.

The asymmetrical room was an obvious add-on, made with cheaper materials and less skill than the rest of the house. It would have made a decent walk-in closet if it had been connected to any of the bedrooms, but instead it grew off the utility room like an architectural tumor.

Bailey set the elliptical machine for a twenty-five-minute workout and sat on the floor next to it. A large dusty trophy

from the Little Miss Sass and Sand Princess Pageant (Gulf Shores, Alabama) sat in the back of the room: an anonymous peak in a mountain range of awards. Bailey carefully twisted off the bottom, and a Snickers bar fell into her lap. The elliptical machine beeped impatiently, and Bailey started pushing the foot pedal with her hand. The distance and calorie counter slowly began to rise as Bailey tore into the candy bar, jolting her body with the satisfying rush of sugar and defiance. From under the futon, she pulled a Kindle she’d won in an online photo contest and swiped to page seventy-eight of Looking for Alaska. A poster-sized glamour shot—Bailey’s most recent pageant photo—looked down at her from across the room, and Bailey stared back, mocking it as she finished the candy bar in an earnest attempt to destroy the girl in the photo from the inside out.

Meanwhile, Miranda took a worn overnight bag from the cabinet over the washing machine and caught a glimpse of herself in a mirror. Her highlights needed some serious attention. Her hairdresser, Garo (who also styled Channel 7’s popular new weather girl, Giselle Lopez-Beard), had overdone the blond streaks in Miranda’s mocha hair, making her look like a jaundiced zebra. Thank God her body still rocked. Despite having three kids, her boobs were holding up pretty well. Having one small B-cup and one full C was a constant source of embarrassment, but pregnancy rounded them both out to a satisfying and nearly symmetrical D. At seven months, Miranda had barely gained twenty pounds. Although she was dangerously close to her lifetime high of one forty-seven, she was determined not to reach it.

“Not bad,” she said, rubbing her belly. She turned to the side and shot a quick, furtive look at her butt. Every pregnancy had expanded her backside a little bit. She didn’t like to dwell on it, but she did want to be aware of any changes. Miranda Ford wasn’t dumpy, but at five foot four, she certainly could not afford to get any wider. One more baby and she would likely have to permanently go up to a size six, and the thought of that was more depressing than having another boy.

Pretty Ugly: A Novel

Pretty Ugly: A Novel